Introduction

Don’t buy properties with high rates of depreciation. It’s a mistake to think that higher depreciation is a good thing. Wrong. It is the complete opposite in fact. You should instead, purposefully seek out properties with the lowest rates of depreciation.

In this presentation I’ll show how massive a difference it makes in just a few short years. I’ll show how the maths works and show why property developers and all pushers of new property have got it horribly wrong.

The importance of growth

OK, let me start by saying that property investing is all about capital growth. It’s what makes investors truly wealthy. It is without doubt the most important part of property investing.

“Capital growth is like sitting on your hands creating wealth”

Terms

Now, there’s another term for capital growth, it’s called appreciation. When an asset appreciates in value, it means it is becoming more valuable.

- Appreciation

- Becomes more valuable over time

- Good

- Depreciation

- Becomes less valuable over time

- Bad

Depreciation is the complete opposite. When an asset depreciates it is losing value.

Clearly appreciation is good and depreciation is bad. Which means…

“There’s no such thing as depreciation benefits – it’s a contradiction”

What is depreciation?

Alright, let me explain briefly what depreciation actually is. You see, most investors have a very simplistic view of what depreciation is, they think of depreciation as simply a claim they make on their tax returns, some paperwork, a kind of tax trick. They think it’s a government hand-out, a thank-you from the ATO for being a property investor.

“Depreciation is not a government hand-out”

It’s nothing like that. It’s a legitimate claim made for … a … loss. And the loss is real. It’s not just a tax trick.

Let me back up a bit. There’s this fundamental concept of taxation.

- Income $10

- Expenses -$7

- ==========

- Net profit $3

You only pay tax on net profit. Expenses are subtracted from income to come up with net profit.

The same is true for individuals. You can deduct expenses directly related to earning your income. For example, you may have a uniform you wear for work that needs to be dry cleaned. That cost of dry-cleaning would be tax deductible.

And the same is true for running a business, for example, a business that provides accommodation – property investing.

- Rent $10

- Expenses -$7

- Mortgage interest

- Property management

- Council rates

- Insurance

- Repairs & maintenance

- Depreciation

- ==========

- Net profit $3

Your property has expenses which are deducted from rental income and you pay tax on the net profit.

Now, one of the expenses a property incurs, gradually over time, is depreciation. The building deteriorates. It ages. It doesn’t look as flash as what it was on day one when it was built. It’s looking a little run-down, a little tired, perhaps less shiny. So, it’s worth less value.

It’s not just some airy-fairy concept or tax law designed to give property investors a leg-up. As buildings age they become less valuable.

Repairs & Maintenance

Depreciation is different to repairs and maintenance.

Repairs and maintenance are costs you incur immediately. It might be worn carpet or sun-damaged window blinds. Maybe the hot water cylinder dies and needs to be replaced. These are expenses you need to pay for right away and can claim against income on your tax.

But depreciation is a bit different. Something becomes less valuable as it ages, even before it needs to be replaced.

The building itself is part of this and all its fixtures and fittings like the rangehood in the kitchen or the A/C unit. All these things become less shiny over time. The tax office allows you to claim the deterioration of the building as a tax deduction to reflect the new age and therefore new value of the building.

Example

Let me walk through an example. Sorry, I have to do this to get to the main point.

- Back deck = $50,000

- Expected lifetime = 25 years

- Depreciation claim = $2,000/year

- Gross salary = $85,000

- Taxable salary = $83,000

- Marginal tax rate = 32.5%

- Tax saving = $650 (i.e. 32.5% x $2,000)

- After lifetime, total tax saving = $16,250 (i.e. $650 x 25 years)

Let’s say you have a rental property with an awesome deck out the back worth $50,000. And the deck is believed to have a lifetime of 25 years according to the ATO. You can claim $2,000 a year in depreciation for the next 25 years. Now there are other options, but I want to keep this simple.

Let’s say you earn $85,000 a year from your job. Instead of declaring an income to the ATO of $85,000 you’re allowed to declare an income of only $83,000 because you’ve claimed $2,000 in depreciation. That means you get taxed on a lower amount. You pay less tax. You’re not being taxed on an income of $85,000 you’re being taxed on an income of $83,000.

Now at the time I’m recording this, the marginal tax rate for a salary of $85,000 is 32.5%. Which means your tax saving by claiming this $2,000 of depreciation on the deck would be $650. That’s 32.5% of $2,000.

By claiming depreciation on the deck, you’ll have $650 more in your bank account than if you didn’t claim it. And you can do that every year for 25 years. It will sum up to a tax saving of $16,250 by the end of year 25.

Why claim depreciation

Depreciation is a way in which the gradual deterioration of your investment property can be claimed bit by bit. So, you’re not getting a free tax saving. It is costing you. As the property deteriorates, you’ll spend a lot more on maintaining it than you’ll recover in tax savings.

For the example I just gave, the property will cost you 3 times as much in deterioration as the tax savings. You take 1 step forward and 3 steps back.

- Each year

- $2,000 deck depreciation claimed

- $650 tax saving

- $2,000 deck value loss

- Net deck position -$1,350= $650 – $2,000

So, although in the 1st year you have an extra $650 in your bank account. Your deck is now worth $2,000 less than what it did a year earlier. It has aged by one year. Your bank balance may be showing that you’re better off by $650. But your net position is actually worse off by $1,350 because of depreciation.

Although there’s a tax saving which makes those losses less extreme, they’re still losses, so you want to minimise them, not maximise them. And that’s the key point I’m trying to make:

“Depreciation is a bad thing. It is something to be minimised”.

You don’t want maximum depreciation. You want minimum depreciation. In other words, the term ‘depreciation benefit’ is a contradiction, there’s nothing beneficial about depreciation to a property investor.

Selling

Now some of you cunning smarty strategists might be thinking, “How about I claim all the depreciation I can, and sell the property before anything fails. That way I don’t have to pay for fixes and I still get to claim depreciation”.

It doesn’t quite work as well as you’d hoped. You’ve missed the point about what depreciation actually is.

Firstly, not every part of your property will fail at the same time. You don’t know which year it will be. You can’t sell your property just before everything falls apart. So, that strategy is not practical.

But secondly, and more importantly, just because nothing has failed doesn’t mean the building has the same value as it had when you bought it. This is the whole point about depreciation. The next buyer will offer you less money in consideration of the building’s age.

And thirdly, when you sell the property, you pay extra capital gains tax in proportion to the amount of depreciation you’ve claimed over the life of ownership of the property.

- Random failure times

- Building value decreases

- Depreciation added to CGT

An example

- Bought = $400,000

- Depreciation claimed = $30,000

- Owned = 5 years

- Sold = $600,000

- Capital gain = $230,000

- CGT discount = 50%

- Marginal tax rate = 40%

- CGT = $46,000 (i.e. 50% x $230k x 40%)

So, let’s say you bought a property for $400k and owned it for 5 years. Over that time, you claimed $30,000 in depreciation. Then you sell it for $600,000. You think the capital gain is $200,000. But the amount you claimed in depreciation is added back to that capital gain so your capital gain is actually $230,000.

In other words you’re not paying capital gains tax on a gain of $200,000 you’re paying capital gains tax on an amount of $230,000.

Now because you owned the property for more than 12 months, you get the capital gains tax discount which at the time of writing is still 50%. So, you’re paying tax at your marginal rate on half of that $230,000 which works out to be a CGT bill of $46,000.

There are other things you can claim to reduce the capital gain such as certain buying costs and costs associated with selling. But I’m simplifying it to highlight where depreciation fits in to the calculation of CGT.

The main point

I’m not saying you want the most amount of depreciation. Or not to claim depreciation. What I’m saying is, you should target properties with limited depreciation. Limiting depreciation is not a decision you make at tax time. It’s a decision you make at the time of choosing what property to buy. After purchase, during ownership, the degree of depreciation your property experiences, is out of your control. Claim it all as it happens. But just don’t choose to buy a property which has a lot of depreciation… “potential”.

Budgeting for replacements

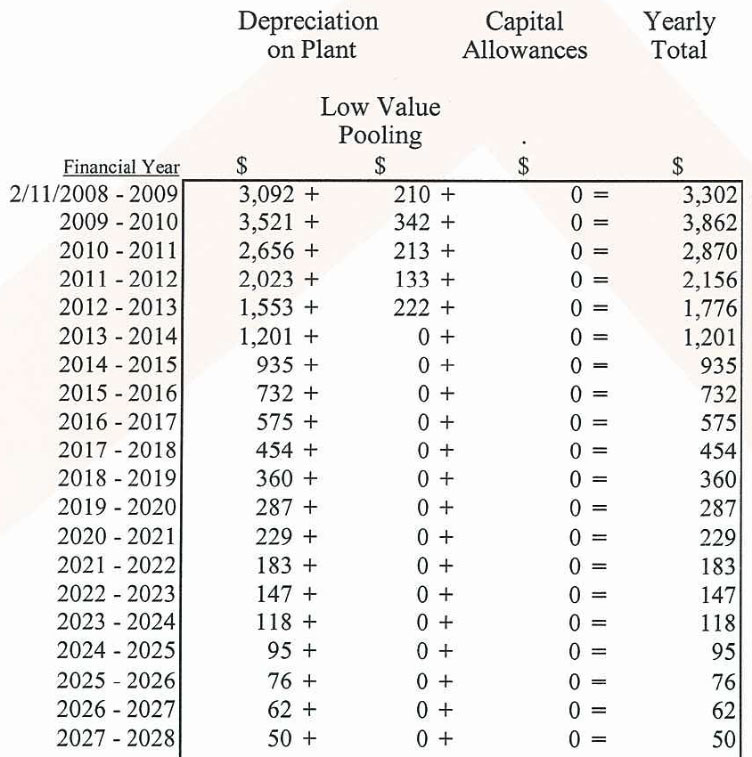

Now, in order to claim depreciation, you need a depreciation schedule. A depreciation schedule is a list of claims you can make over the life of ownership of your property. Here’s an examples…

You can hire the services of a quantity surveyor to draw one up for you. They come at a cost of course. But they’re worth it. And not just for the tax claims.

One really important thing the depreciation schedule provides for a long-term property investor is an estimate of how much money you need to set aside for replacing items when they drop off.

Keep in mind that your tax savings will never be enough to cover the cost of replacing the depreciable items. That’s because the tax saving is only a portion of the item’s value. You still have to come up with the remainder from your personal earnings or rent.

Bad advice

OK, back to the main point of this article: depreciation is working to reduce the value of your asset. If it’s a bad thing, how did we get this term “Depreciation benefits”?

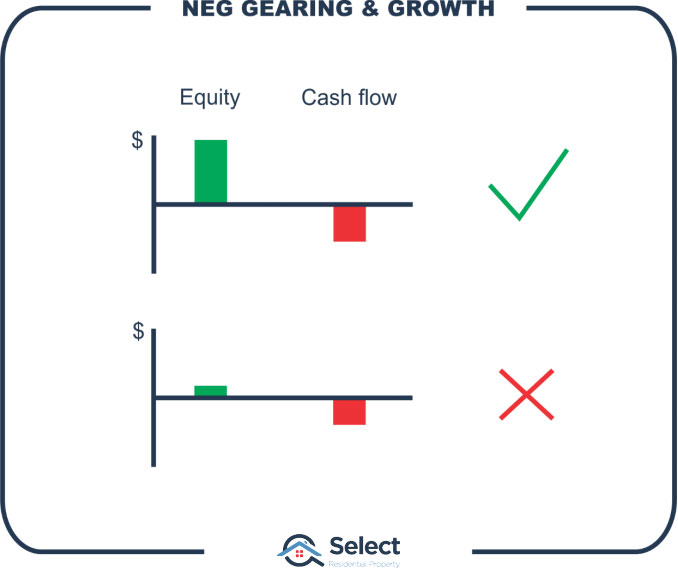

Those Australians paying a lot in tax might have sought council from an accountant who recommended buying a negatively geared investment property with a high rate of depreciation.

That’s not bad advice, so long as the investment property appreciates in value and at a reasonable rate. But if it’s not experiencing growth or insufficient growth, then you’re actually losing money. The fact you can claim that loss on your tax return is little consolation, you’re still losing money.

You’re better off continuing to pay higher tax than to buy an investment that doesn’t grow. The goal isn’t to become so poor you pay less tax.

“You’re not hurting the ATO by paying less tax”

Owning a negatively geared property and claiming depreciation is only worthwhile if the property grows in value and by a significant amount. And here’s the most important thing to remember about depreciation…

“The higher the depreciation is, the lower the capital growth will be”

How depreciation hurts growth

The reason why high depreciation leads to low growth is because most of your money is being allocated towards the dwelling, the building, which deteriorates. The land appreciates, the building depreciates. So, allocate more of your money to land, which is the asset. And allocate less to the dwelling, which is the liability.

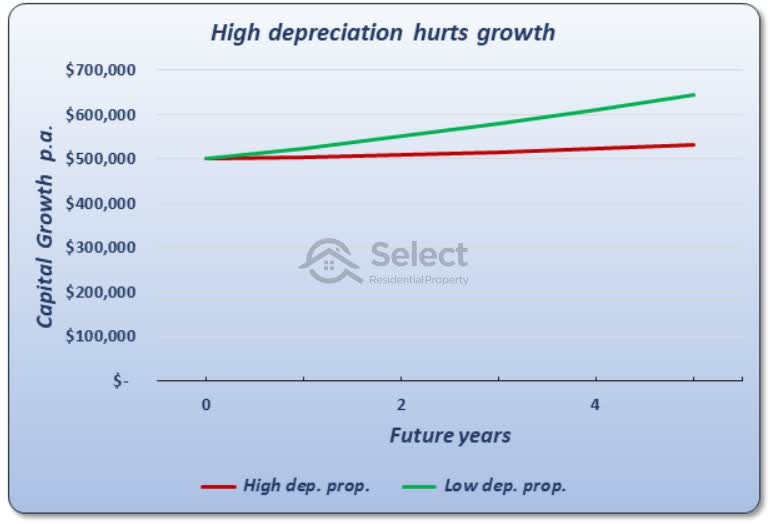

Consider this example of 2 properties. Imagine both worth $500,000. But the make-up of each is different.

- Low dep. prop. $500K

- $400k land value

- $100k building value

- High dep. prop. $500k

- $200k land value

- $300k building value

One is old and its building has already depreciated significantly to only $100,000. But it’s on a more expensive block of land worth $400,000. This older property will have lower rates of depreciation.

The 2nd property is worth the same amount, but most of its value comes from the dwelling which is new and cost $300k to build. The land is cheaper at only $200k.

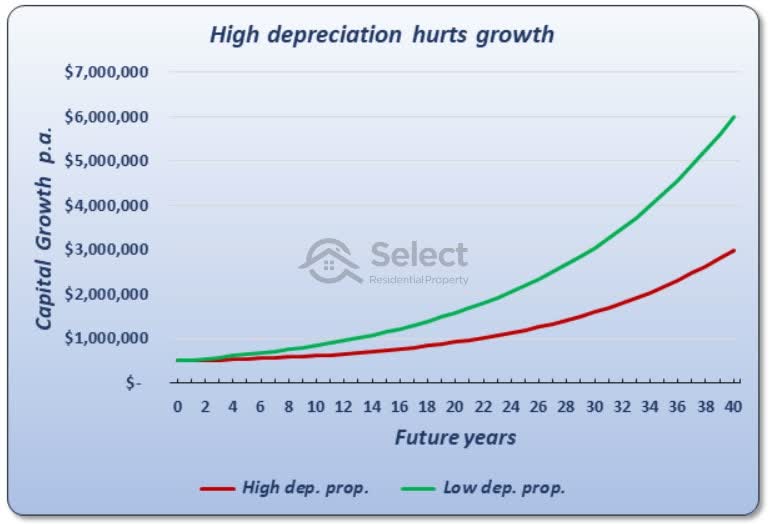

Now imagine both blocks of land appreciate at the exact same rate. And imagine both dwellings depreciate at the exact same rate. Here’s a chart showing the difference in growth over a 5-year period for these two properties.

Both of them started at $500,000. But the red one had virtually flat growth, while the green one grew by over $100,000.

The tricky part

Here’s the thing you need to get your head around. Although both of these properties had the same growth rate… in land value and both had the same depreciation rate, there was a big difference in overall performance because of the break-down of land and building – of asset and liability.

The new property (red) had a higher percentage of its price associated with the building which depreciated and thwarted overall growth.

The old property (green) was mostly land value. The building was already old and had depreciated to a lower value.

Keep in mind both properties were the same price and had the same rate of appreciation in their land. Both also had the same rate of depreciation in their buildings. But one performed much better than the other simply because it had less depreciation.

- Low dep. prop.

- $144k growth

- $13.5k dep tax refund

- $157.5k tot gain

- High dep. prop.

- $30.5k growth

- $40.5k dep tax refund

- $71k tot gain

- Difference between props

- $113.5k growth

- $27k cash-flow

- $86.5k net in favour of green

If you had picked the old green low depreciation property instead of the new red high depreciation property, you would have had much better capital growth – $144k versus $30k.

But you would have had worse cash-flow – $13k versus $40k.

Overall however, you would have been better off buying a low depreciation property by $86,000 in only 5 years.

Long-term

BTW, here’s how the race would play out over 40 years…

If you had picked the green low depreciation property instead of the red high depreciation property, you would have had much better capital growth – $144k versus $30k.

For the entire period both properties had the same growth and depreciation rates. There’s a $3m difference in values after 40 years. All from one simple decision made 40 years earlier.

Do not buy new property. It has much higher rates of depreciation than older property.

How did we get here?

It’s amazing the difference isn’t it. How on earth did we ever get this term, “depreciation benefits”?

Accountants

Well, I suspect one of the ways in which investors may have acquired this term was from misunderstanding tax advice from their accountant. The idea of buying a negatively geared property from a tax efficiency perspective is to convert income which is taxable into equity growth which isn’t. Many investors missed the last point – the growth.

It’s also possible that accountants assumed the growth for property would be the same regardless of whether a property had a high or low rate of depreciation. But that’s not true. The higher the rate of depreciation is, the lower the growth potential.

Now that’s one possible cause for the misnomer “depreciation benefits”.

Developers

I suspect the biggest cause of confusion for property investors about depreciation comes from property developers and their project marketers.

Older properties have less depreciation. New property has a whole life of depreciation ahead of it. The entire value of the property can be depreciated. So, this is packaged up as a “bonus” and marketed hard to property investors.

The thing is, as you’re well aware, depreciation isn’t a bonus. On the contrary, it is a negative. Remember, depreciation is bad. Every dollar of depreciation is bad.

“Investors should buy properties to maximise appreciation and minimise depreciation”

That means if you had the choice to buy a new property or an old one in the same booming suburb, you should choose the old one because it will have less depreciation. Old will outperform new – all other things being equal. It’s a mathematical certainty. If you don’t believe me, check out this presentation:

“Buy new properties not old – WRONG!”

It explains why it is impossible for new property to outperform old, all other things being equal. It’s not a matter of opinion. It’s a mathematical fact that new property simply cannot outperform old property – if the primary difference between the properties is their age.

Depreciation scale

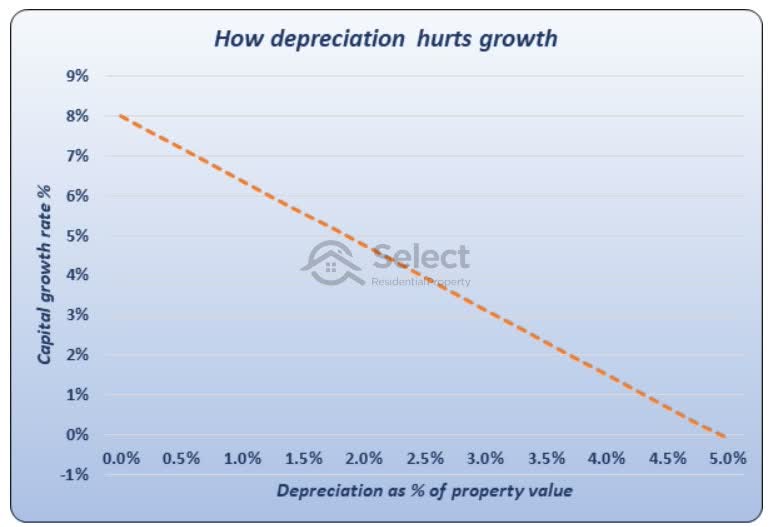

Some of you might be wondering, “how much depreciation is too much?” Great question, I’ve done some rough calcs.

This chart plots the estimated capital growth relative to the degree of depreciation. The orange dotted line estimates the relationship between depreciation and capital growth. This chart assumes a baseline capital growth rate for land of 8%. That’s the growth rate of vacant land which has nothing to depreciate.

The scale of depreciation is across the bottom horizontal axis. This is depreciation as a percentage of the property’s total value. So, for example, if you’re looking to buy a property worth $500,000 and the potential depreciation you could claim is around $10,000, then the rate of depreciation, shown across the bottom of the chart, would be 2%, which is seen around the middle of the chart.

- $500k property

- $10k depreciation

- 2% depreciation

- Around 5% capital growth

If you run your eye straight up from 2% to where it meets the orange dotted line, you’ll see that the capital growth rate is a bit below 5%. Given the baseline is 8%, you’d have about 3% lower capital growth due to the high level of depreciation.

You should be targeting properties where the depreciation claimable from year 1 is less than 0.5% of the property’s value. That’s at the extreme left edge of this chart. For example, if you can only claim $2,000 for a $500k property, the depreciation would only be 0.4% of the property’s value, which is quite good.

What to look out for

Alright, wrapping up, the worst properties for depreciation are new properties. They have only just started deteriorating. They have 100% of their construction cost to go.

Don’t be lured into big tax deductions. As soon as you take your eyes off capital growth, you’re at risk of making a mistake property investing. You need to pursue growth above all other factors with the possible exception of risk. Whatever tax deductions you can claim along the way will be simply a bonus.

Remember that appreciation is good and depreciation is bad. When choosing a property to invest in, aim to maximise appreciation and minimise depreciation.

Now I realise this has been a bit of a mind-bender. If the penny hasn’t quite dropped about this concept, there are another couple of topics in this series which will help clarify with good examples: